Think that’s weird?

Well, ant researchers have

determined that the Large

Supercolony is part of an

even larger megacolony that

also includes ants on the

other side of the Atlantic and

Pacific Oceans. If you were

to drop ants from the Large

Supercolony in California into

a nest of Argentine ants in

Japan or into a nest along the

coast of the Mediterranean

Sea in Europe, the residents of

those colonies would not attack

the newcomers as strangers.

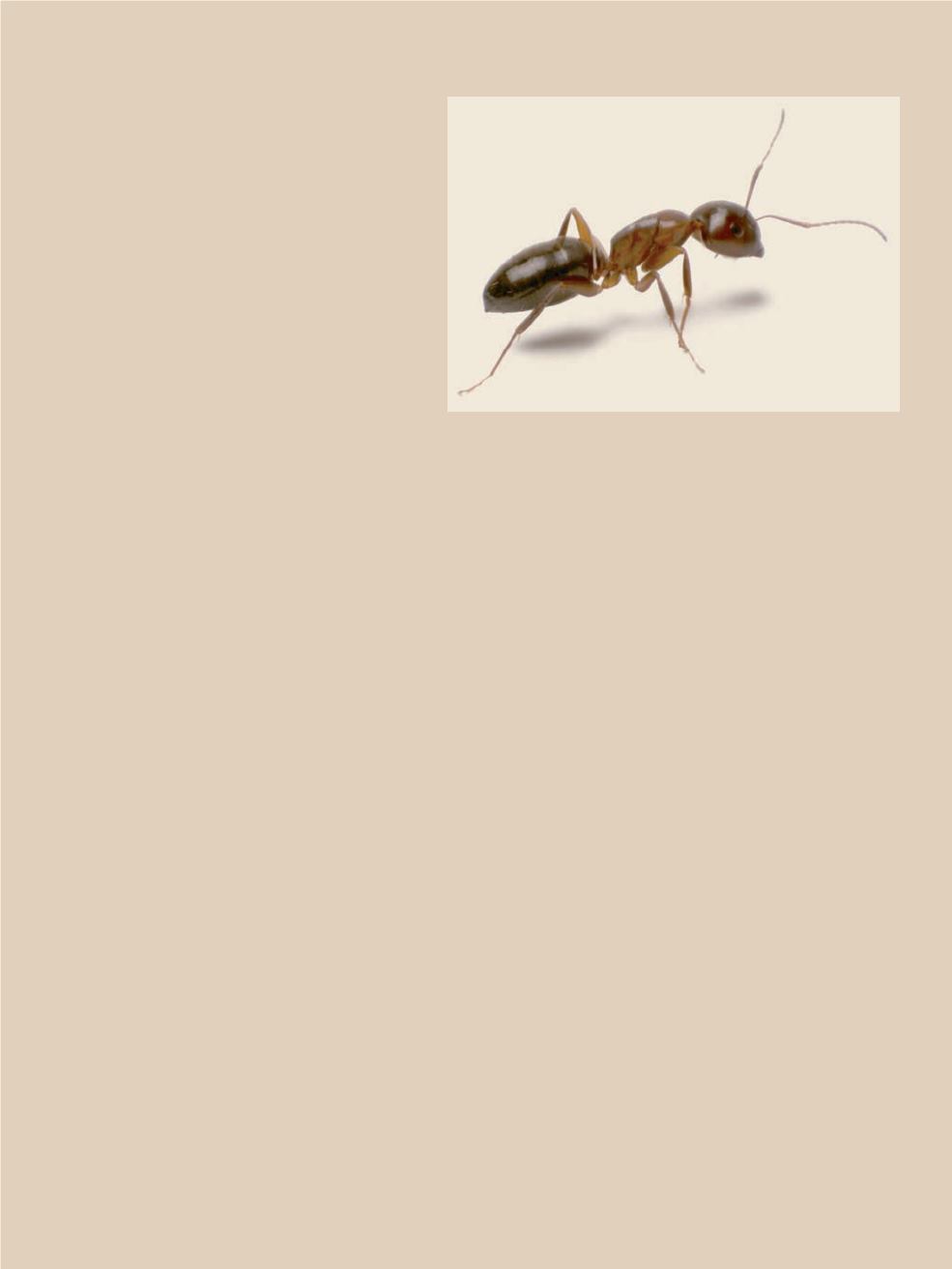

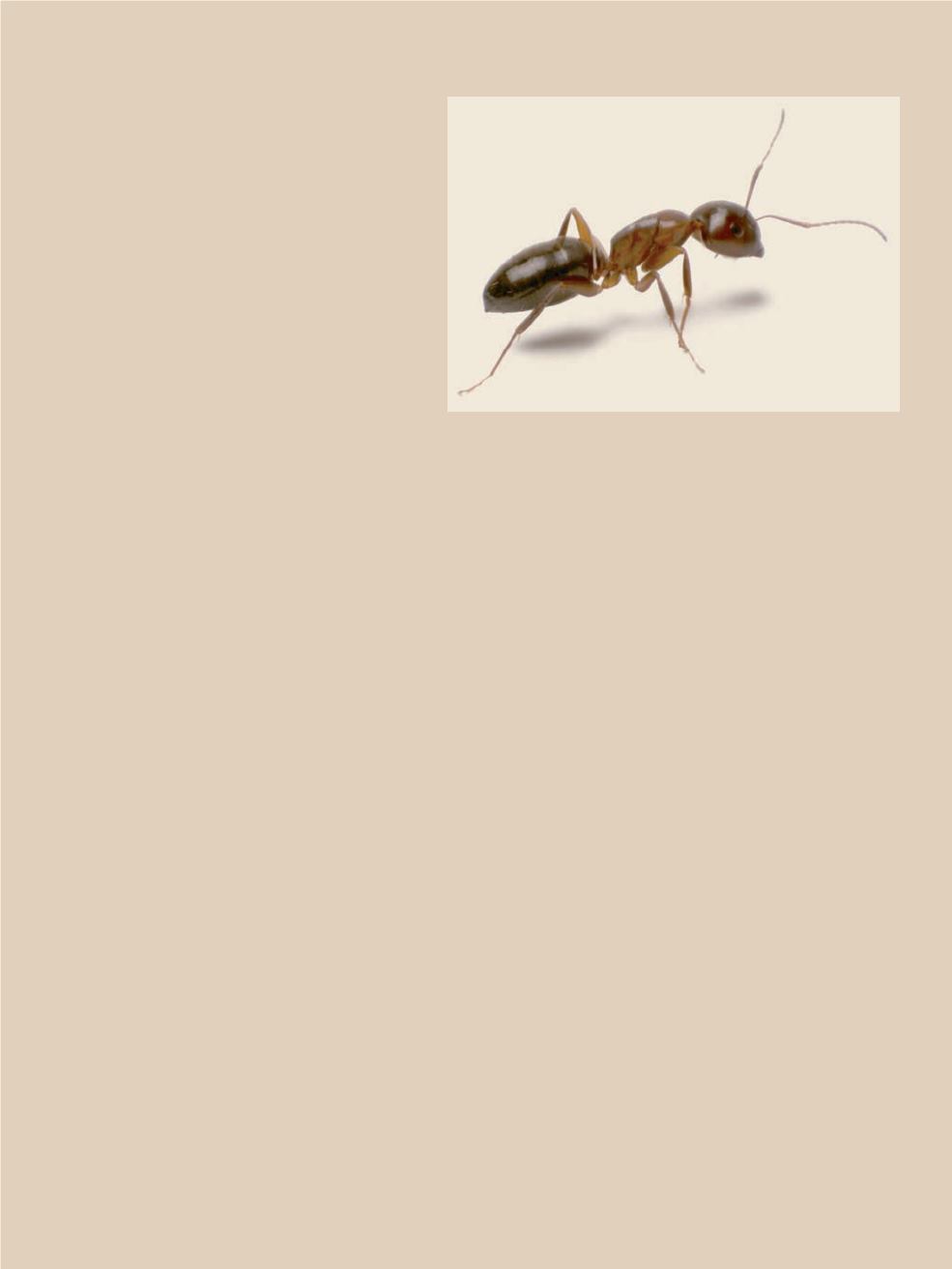

All ants use chemical communication—smell—to tell friend from foe. As

long as the new ants smell right, the others accept them as colony mates.

Moffett says that “the [Argentine] ants’ aggressive response to each other’s

body smell acts like an immune system—killing all outsiders . . . no matter

how big the colony grows.”

Ants communicate through scented chemicals called

pheromones. Ants use the tips of their antennae to smell

the pheromones, of which there are about ten to twenty

types that all ants in the colony recognize. Chemically

communicated messages tell the other ants many things,

including where food is or that it’s time to attack prey or

to defend the colony.

In an ant subdivision outside San Diego, California, however, it’s all-out

war. Here is where the border of the Large Supercolony meets the borders

of three other ant supercolonies. Melissa Thomas, an evolutionary biologist

and ant researcher at the University of Western Australia, has estimated

that as many as fifteen million ants die in skirmishes along this border in a

six-month period.

How do such megacolonies form, and what makes them work? To

understand the Argentine ant, you must first understand the sugar ant back

home in Argentina.

a.k.a. t

he

s

ugar

a

nt

Home is the flood plain of the Paraná River, which flows through

woodlands in Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina. In this region of South

46

S

MART

AND

S

PINELESS