Page 5 - My FlipBook

P. 5

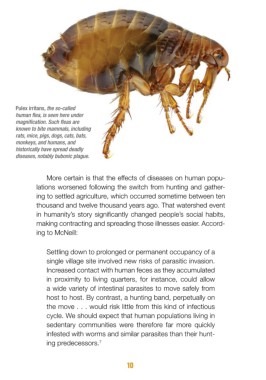

Pulex irritans, the so-called

human ea, is seen here under

magni cation. Such eas are

known to bite mammals, including

rats, mice, pigs, dogs, cats, bats,

monkeys, and humans, and

historically have spread deadly

diseases, notably bubonic plague.

More certain is that the effects of diseases on human popu-

lations worsened following the switch from hunting and gather-

ing to settled agriculture, which occurred sometime between ten

thousand and twelve thousand years ago. That watershed event

in humanity’s story signifi cantly changed people’s social habits,

making contracting and spreading those illnesses easier. Accord-

ing to McNeill:

Settling down to prolonged or permanent occupancy of a

single village site involved new risks of parasitic invasion.

Increased contact with human feces as they accumulated

in proximity to living quarters, for instance, could allow

a wide variety of intestinal parasites to move safely from

host to host. By contrast, a hunting band, perpetually on

the move . . . would risk little from this kind of infectious

cycle. We should expect that human populations living in

sedentary communities were therefore far more quickly

infested with worms and similar parasites than their hunt-

ing predecessors. 7

10